by Zach Wilson, GLIFWC Forest Ecologist

Spring and summer months in Ojibwe Country heralds the return of vibrant amphibian activity, notably among frogs and the one species of toad, the American toad (Anaxyrus americanus). Wetlands are bursting with life, and the calls of our frog friends are singing so loudly that at times they seem deafening. These species enrich ecosystems and serve as vital indicators of environmental health.

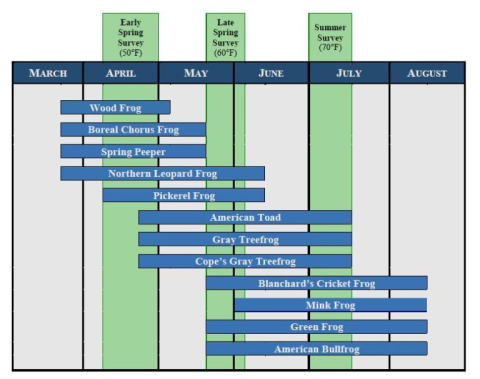

Established in 1981, the Wisconsin Frog and Toad Survey is a citizen-based monitoring program aimed at assessing the status, distribution, and long-term population trends of Wisconsin's twelve frog and one toad species. The survey employs auditory surveys along approximately 100 permanent roadside routes, each comprising 10 listening stations situated near diverse breeding habitats such as ponds, lakes, marshes, and wooded swamps. Volunteers conduct these surveys three times annually—early spring, late spring, and summer—to capture the breeding calls of various species. Several GLIFWC member tribes conduct these surveys throughout the Northwoods, documenting changes over time.

Listening to the forest beings is part of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and marks the changing seasons. Ojibwe elders have long advised that when spring peepers start calling in ziigwan, the walleyes are spawning and it’s time to go spearfishing.

Amphibians, including frogs and toads, are often termed "indicator species" due to their sensitivity to environmental changes. Their permeable skin and aquatic breeding habits make them susceptible to pollutants, habitat alterations, and climate variations. Monitoring their populations provides invaluable insights into ecosystem health.

The extensive data collected by volunteers has unveiled several noteworthy trends:

American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus): Once a species of concern, recent data indicate increasing populations, suggesting successful conservation efforts.

Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens): The survey has documented a long-term decline in their numbers, highlighting potential environmental challenges affecting their habitats.

Blanchard's Cricket Frog (Acris blanchardi): Citizen scientists have reported new populations along the Mississippi River and areas where they hadn't been observed

in over three decades, pointing to possible habitat recovery and conservation successes.

Incorporating TEK with conventional scientific approaches enriches our understanding of amphibian populations. TEK emphasizes the value of local and indigenous knowledge systems, fostering a deeper connection to the land and its inhabitants. In Wisconsin, community engagement through programs like frog and toad monitoring exemplifies this integration. Volunteers, often referred to as "froggers," contribute to scientific research while strengthening their bond with nature. This participatory approach ensures that conservation strategies are culturally relevant and locally supported.

Springtime in Wisconsin offers a symphony of amphibian calls, each note a testament to the health of our environment. Through initiatives like the Wisconsin Frog and Toad Survey, combined with the principles of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, we gain a comprehensive understanding of these species' roles and the broader ecological narratives they represent.

To learn more about conservation efforts and wildlife monitoring, see the Wisconsin Frog and Toad Survey at https://wiatri.net, or check with your local tribal natural resources department and volunteer to assist in conducting surveys.