Indigenous knowledge, also known as Indigenous ways of knowing or Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), is a philosophy and worldview that reflects the language and lifeways of Indigenous peoples. Here in the Ceded Territories of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan, this knowledge is known as Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing or, as Red Cliff elder Marvin Defoe says, “Anishinology.” Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing encompass the precise knowledge and understandings of landscape ecology, movement and behavior of fish and wildlife, medicinal plant knowledge, seasonal change, and harvest traditions. This knowledge base has sustained Anishinaabe people for millennia in the Great Lakes region and contributed to their identity as a distinct culture.

GLIFWC works to integrate the language, culture, and philosophy of Anishinaabe people into contemporary science and policy so that the management of fish, wildlife, and natural resources is culturally relevant and sustainable. GLIFWC honors and protects our non-human relatives in accordance with Anishinaabe values, while at the same time, honoring and protecting treaty rights and tribal sovereignty within the Ceded Territories of 1836, 1837, 1842, and 1854.

GLIFWC has been transcribing and summarizing interviews and comparing observations with the western science-based results of the vulnerability assessment. The interviews are also providing GLIFWC with insights and observations not captured through the standard techniques of scientific ecological knowledge gathering. Increasing and decreasing trends in particular beings/species populations are becoming more apparent as additional interviews occur. From the interviews so far, the most commonly mentioned species are white tailed deer, paper birch, northern white cedar, wild rice, and various berries, with interviewees noting paper birch as having the biggest decrease.

Anishinaabe Insights: A closer look at TEK - Indigenous knowledge finds its way into science & policy

By Michael Waasegiizhig Price, GLIFWC TEK Specialist

Originally published in Mazina’igan, Winter 2022-2023

In November 2021, the President of the United States issued an Executive Memorandum ordering all federal agencies to integrate Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge (ITEK) into federal decision-making. This memorandum is meant to strengthen relations between federally recognized tribal nations and the federal government, as well as tap into the rich wisdom that Indigenous people possess about the landscape. But what does this really mean? The term, Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), has been around since the mid-1990s. It refers to Indigenous knowledge and wisdom that have existed for thousands of years among Indigenous communities. A good definition: Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is a body of localized ancestral knowledge and wisdom about the landscape, passed down through the generations in the form of stories, songs, placenames, and traditions, that have sustained a people for millennia and contributed to their identity as Indigenous people. Knowledge of trees, animals, waterways, and seasons contribute to the ability of a people to subsist and thrive in a particular landscape. But, just as there are diverse landscapes, so are the diverse knowledges of Indigenous peoples. Anishinaabe people are experts on wild rice beds in Minnesota; Lakota people are experts on buffalo rangeland in the Dakotas; the Inuit people are experts on arctic tundra and pack ice. Federal decision-making taps TEK.

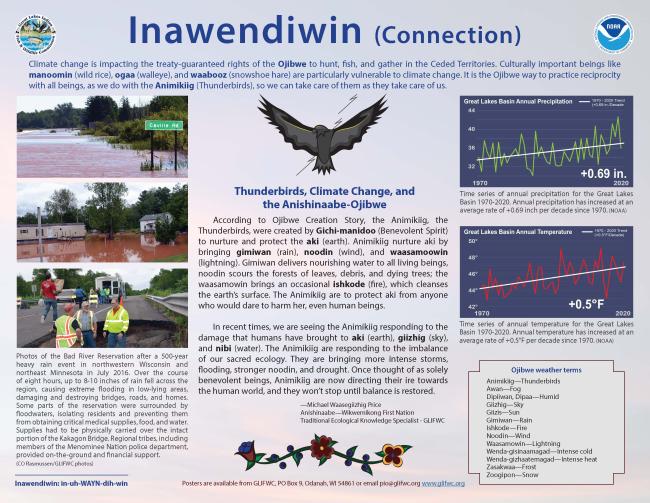

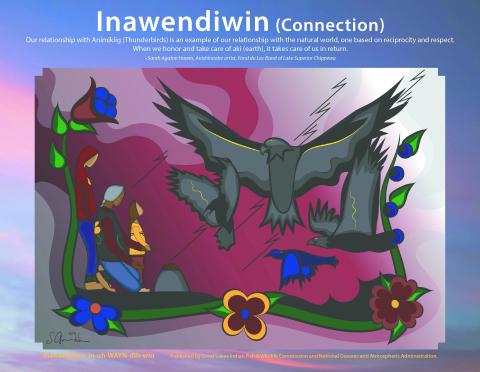

Through an innovative partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), this double-sided poster features art by Sarah Howes, Fond du Lac Ojibwe. The poster explores climate change through a cultural, scientific, and practicable lens as native communities increasingly experience extreme weather events.