Both Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and Scientific Ecological Knowledge (SEK) play a critical role in GLIFWC's work protecting culturally important plant and animal beings in the Ceded Territories. In the Climate Change Program, we seek to elevate TEK and let it guide our work. We also attempt to interweave the two knowledges in a good way in all of our work and recognize that both knowledge systems will be important in helping GLIFWC and its member tribes adapt to climate change.

Climate change is bringing warmer air and water temperatures, extreme storms, and changing winters to the Ceded Territories. These rapid changes, among others, are making life harder for many culturally important plant and animal beings that GLIFWC member tribes have had relationships with for thousands of years. These changes will also make it harder for GLIFWC member tribal communities to practice their off-reservation treaty rights to hunt, fish, and gather in the Ceded Territories.

Some of the changes we will experience in the Ceded Territories include:

Less snowpack and/or different type of snowfall

Snow depth is projected to decline due to increased temperatures, with more precipitation falling as rain instead of snow and decreased winter precipitation in general. This decline in snow will affect countless cultural traditions, including storytelling and cultural activities, including the traditional game of Gooniikaa-Ginebig Ataadiiwin (snow snake).

Earlier ice melt and thinner winter ice

Many cultural activities will be significantly affected by reduced ice cover. Spearing through the ice for name (sturgeon), ginoozhe (northern pike), and maashkinoozhe (muskellunge) for food and ceremonies is a cultural activity passed down through generations. Recently, tribal members have been recording less ice cover:

“In the last 3 years we haven’t had no ice… I used to make my living fishing on the ice in the wintertime… hard work and all that, but in the last, say, 3-5 years we never had no ice. When I say no ice, I don’t mean just Bass Island, I mean where we could go 25 miles right straight out to Outer Island [Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, northern Wisconsin]. We used to set nets out there, but in the last 5 years, nothing… The last two years, the ferry boats run all year round now.” —Joseph Duffy

Heat waves

The Ceded Territories will experience more extremely hot days. A heat wave rolled across the Ceded Territories during the 2023 ricing season. With temperatures well into the 90s, many manoomin (wild rice) harvesters were heavily impacted. Even with additional drinking water and shorter time on the lakes, some still experienced heat-related illnesses like heat exhaustion. The manoomin also ripened unevenly in the heat.

Increase in rainstorms/risk of flood events

In 2016, the Mashkiiziibiing (Bad River) area received a 500-year rain event that dropped 8-10 inches of rain in an 8-hour period and caused the Bad River to rise over 27 feet. This event washed out roads, destroyed homes, caused power outages, and left community members stranded without access to medical care, medical supplies, food, or water. High water events of this type are projected to become more frequent as climate change continues.

Drought

More precipitation is projected to fall in bigger events, with drier periods between storms. This can be hard for plant and animals beings that rely on consistent water sources:

“Now the problem that I’m seeing with sugar maple is they’re really incredibly sensitive to drought cycles... you can stress the trees. And especially if you’re tapping them, they can go. You can tap them if you have one bad season of drought. But you have lower water quantities over a period of time... it really has an effect on them.” —Niso-asin Sean Fahrlander

Changes in Habitat and Beings

Many beings of interest to GLIFWC’s member tribes will be affected by climate change in the upper Midwest Ceded Territories, regardless of which emissions scenario unfolds. Many of these will decrease in abundance and/or shift their ranges. In some cases, ranges may shift out of the Ceded Territories entirely, putting relationships held with Ojibwe people for centuries at risk. The most vulnerable being in the GLIFWC vulnerability assessment, manoomin, is a being closely connected to the identity of Ojibwe people and is already experiencing declines due to climate change. Dawn White, GLIFWC’s Treaty Resource Specialist, is seen here harvesting manoomin.

For more information on climate impacts in the Ceded Territories, see Aanji-bimaadiziimagak o’ow aki, the GLIFWC Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment.

Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment Version 2 (Open PDF)

Aanji bimaadiziimagak o’ow aki, the second version of the GLIFWC Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment, is an attempt to weave together Traditional and Scientific Ecological Knowledge to examine the climate change vulnerability of a set of beings in the upper Midwest Ceded Territories by the mid-21st century. The assessment is meant as a resource for GLIFWC’s member tribes and their tribal and non-tribal partners, to help them prepare for upcoming changes and care for those who take care of us.

Ten beings were found to be the most at risk in the vulnerability assessment. All of these are culturally important beings that Ojibwe people have relied on for generations. For more information, read the full assessment linked above.

The Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu, which was developed by a diverse group of collaborators representing tribal, intertribal, academic, and federal entities in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan, provides a framework to integrate Indigenous and traditional knowledge, culture, language and history into the climate adaptation planning process. Primarily developed for the use of indigenous communities, tribal natural resource agencies and their non-Indigenous partners, this Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu may be useful in bridging communication barriers for non-tribal persons or organizations interested in Indigenous approaches to climate adaptation and the needs and values of tribal communities.

The Tribal Adaptation Menu team facilitates workshops across the Ceded Territories and beyond, helping tribes and their non-tribal partners plan culturally driven adaptation projects. In 2024 we completed a series of workshops with tribes and associated National Forests addressing threats to tribal lands and values on National Forest land, including culturally appropriate climate adaptation.

This Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu provides a framework to integrate indigenous and traditional knowledge, culture, language, and history into the climate adaptation planning process.

The Tribal Adaptation Menu is an extensive collection of climate change adaptation actions for natural resource

management, organized into tiers of general and more specific ideas. The Menu also includes a companion Guiding

Rob Croll (GLIFWC) and Sara Smith (College of Menominee Nation Sustainable Development Institute) present an introduction to Dibaginjigaadeg Anishinaabe Ezhitwaad, the Tribal Adaptation Menu (TAM) for University of Wisconsin-Extension.

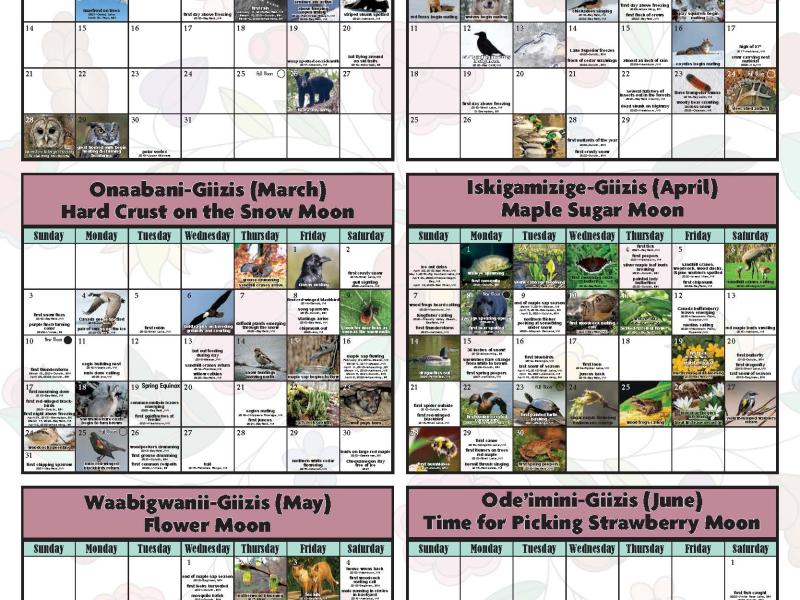

Phenology is the study of cyclic natural phenomena such as the budding of plants, emergence of insects, migration of birds, and thawing of lake ice. Monitoring these seasonal changes on a long-term basis can provide insight into environmental changes associated with climate impacts.

GLIFWC is conducting a phenology study of treaty harvested plant beings at two study sites in the Ceded Territories. The study could provide a better understanding of how changes in the timing of the life cycles of some species might impact traditional harvesting. GLIFWC scientists are recording weekly progress of each being throughout the growing season; we are also collecting traditional stories and observations of Anishinaabe elders and harvesters whose knowledge of these beings has passed through generations.

GLIFWC is also accepting observations from across the Ceded Territories! Help us study phenology and climate change by submitting observations from your location.

The Climate Change team compiles phenology observations from across the Ceded Territories on a calendar, published every two years. Look for the next calendar in 2026!

This is an excellent way to engage your family and classrooms outdoors! What do you see? We look forward to your submissions!

Download and print this form to use in your classrooms or at home! Submit to GLIFWC for prizes.

The Climate Change Program is working on collecting and preserving seeds of traditionally harvested plant species. Seeds collected as part of the project are stored at the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation (NCGRP) in Fort Collins, Colorado, with whom GLIFWC has executed a Material Transfer Agreement.

Ganawenindiwag is a guide that empowers users to grow, promote, and use plant beings specifically from natural plant communities adapted to coastal areas of Gichigami (Lake Superior) to heal and protect Gichigami shorelines. The intent of this planting guide has been to blend different ways of knowing together and to share about plants in a way that intentionally elevates the knowledge and the guidance of Indigenous communities.

The Lake Superior National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) and the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) announce the release of Ganawenindiwag: Working with plant relatives to heal and protect Gichigami shorelines.

Our climate change working group is an interdisciplinary team made up of staff from the Biological Services Division and the Division of Intergovernmental Affairs who perform research, facilitate workshops, conduct outreach, and work collaboratively with partner organizations to better understand how plants, animals, and people can adapt to changing ecosystems. Our findings are shared in GLIFWC publications and professional journals. The Climate Change Team has staff in multiple divisions at GLIFWC.

Pictured is our team at a staff listening session (l-r): Travis Swanson, Forest Ecologist; Rob Croll, Climate Change Program Coordinator; Aaron Shultz, Inland Climate Change Fisheries Biologist; Hannah Panci, Climate Scientist; Travis Bartnick, Wildlife Biologist; Illeana Alexander, Tribal Climate Adaptation Specialist; Allie Carl, Wildlife Biologist; and Cat Techtmann, Environmental Outreach Specialist, University of Wisconsin-Extension. Not pictured: Melonee Montano and Michael Waasegiizhig Price