Ojibwe treaty tribes created the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission in 1984. Our staff serve 11 Ojibwe tribes in support of property rights reserved in treaty negotiations during the mid 1800's. Commonly known as treaty rights, tribal hunting, fishing, and gathering includes public lands and waters in a region called the Ceded Territory of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota.

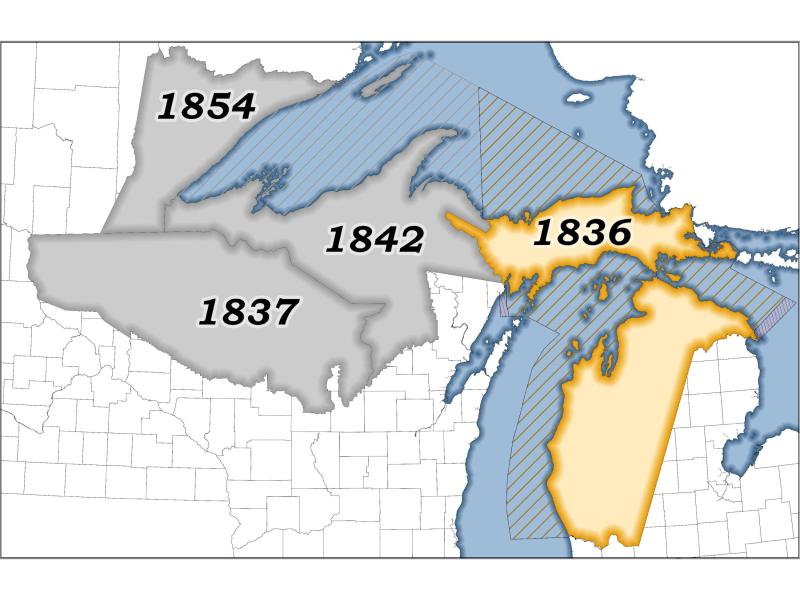

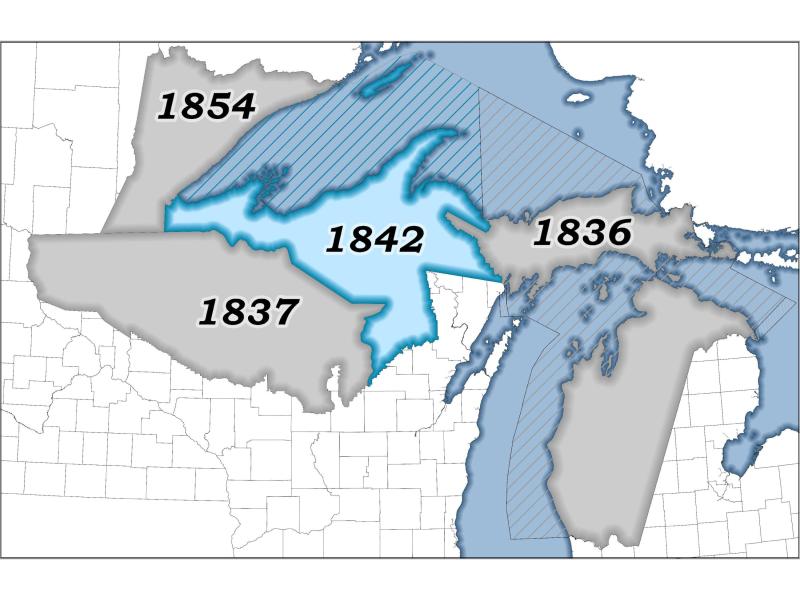

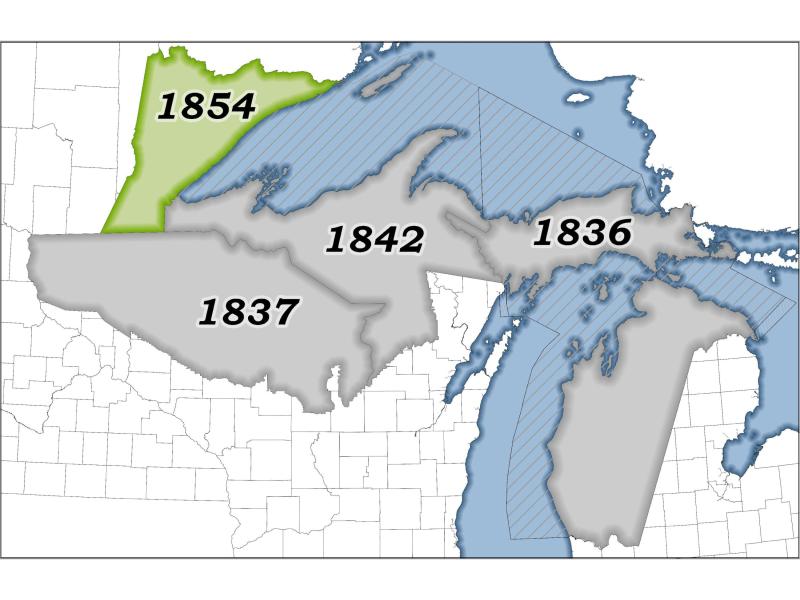

GLIFWC staff assists our member tribes in implementing natural resources assessments and harvest seasons. We also work with partner agencies, organizations and the public on cooperative natural resources enhancement and stewardship. Our work and reactions are rooted in science and traditional ecological knowledge to best serve the next seven generations across the 1836, 1837, 1842 and 1854 Treaty Ceded Territories.

Created for students, agency personnel, and general viewers, this 18-minute DVD presents a brief history of treaty-reserved tribal harvesting rights in the upper Great Lakes region. Viewers are introduced to 21st Century Ojibwe harvesters and the natural resource agency that manages treaty resources on behalf of its Ojibwe member tribes—the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC)

Copyright 2011

Treaties are sacred documents and the supreme law of the land. When the treaties of 1836, 1837, 1842, and 1854 were negotiated by the United States government and tribal leaders, the Ojibwe insisted on reserving the rights to hunt, fish, and gather on the property they were ceding, known as the Ceded Territories. The Ojibwe were never "granted" these rights by the United States; instead, they retained the same rights that they have always had.

The U.S. government facilitated and signed more than 400 treaties with tribal nations across what is now the United States. In the Great Lakes region, the Ojibwe territories now known as Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota gained statehood after treaties were signed. The newly drawn state boundaries, and government policies contained therein, can't overwhelm or overpower the established treaty boundaries. The agreements made between Ojibwe nations and the U.S. within these treaty documents are on equal footing with federal law.

Because treaties outrank and predate state governments, state hunting laws/seasons don’t typically apply to tribal citizens exercising their traditional lifeways. Treaty language and the U.S. Supreme Court agree, native nations have an inherent right to self-rule and self-regulate.

Our member tribes shape our organizational goals through three governing bodies who set the direction and prioritize the work of GLIFWC staff. Through agreements with state agencies, GLIFWC possesses delegated authority to advocate directly with state and federal governments on behalf of the collective commission. GLIFWC member tribes fully retain their inherent and independent sovereignty to govern their members and regulate on-reservation harvests.

Each member tribe holds a seat on the Board which meets bi monthly to discuss harvest recommendations, finances, events, organizational priorities, and hiring.

Following LCO v. Voigt decision, the tribes who were a part of that litigation formalized the Commission's membership.

Great Lakes Indian Fisheries Committee: Five of GLIFWC's member tribes serve on the Fisheries or "Lake" Committee to determine recommendations for commercial treaty harvest.

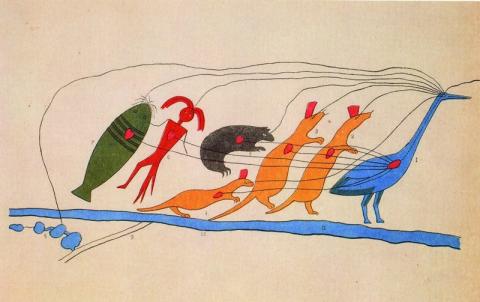

During the late 1840s, rumors circulated among Wisconsin bands that the Ojibwe of the Lake Superior region were destined to be removed from their homes and sent to inland Minnesota. In 1849 a Ojibwe delegation traveled to Washington to petition Congress and President James K. Polk to guarantee the tribe a permanent home in Wisconsin. These delegates carried this symbolic petition with them on their journey.

The animal figures represent the clans, as determined by family lineage, whose representatives made the historic appeal. Other images represent some features of the Ojibweg homeland.

Lines connect the hearts and eyes of the various doodemag to a chain of wild rice lakes, signifying the unity of the delegation’s purpose. This pictograph, originally rendered by the Ojibwe on the inner bark from a paper birch tree, was redrawn by Seth Eastman and appears in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, Vol. 1 (1851).

The following legend details the pictograph’s numbered images. 1. Osh-ca-ba-wis—Chief and leader of the delegation, representing the Crane doodem. 2. Wai-mi-tig-oazh—He of the Wooden Vessel, a warrior of the Marten doodem. 3. O-ge-ma-gee-zhig—Sky Chief, a warrior of the Marten doodem. 4. Muk-o-mis-ud-ains—A warrior of the Marten doodem. 5. O-mush-kose—Little Elk, of the Bear doodem. 6. Penai-see—Little Bird, of the Man Fish doodem. 7. Na-wa-je-wun—Strong Stream, of the Catfish doodem. 8. Rice lakes in northern Wisconsin. 9. Path from Lake Superior to the rice lakes. 10. Lake Superior Shoreline. 11. Lake Superior. (Image reprinted with permission from The Wisconsin Historical Society)

Start with these GLIFWC essentials, and look for curated suggestions throughout this site. Miigwech!

Ojibwe Treaty Rights is a foundational guide to learning more about the Commission's history.

Minwaajimo tells the story of GLIFWC member tribes' treaty struggles and the development of GLIFWC as an intertribal agency designed to assist in the protection and implementation of those rights.

This book explores key events in the history of Ojibwe people in the greater Lake Superior region. Soon after Ojibwe leaders negotiated treaties withe the United States in the mid-1800s.